Agency Is a Scaling Tool

Organizations often treat agency as a risk.

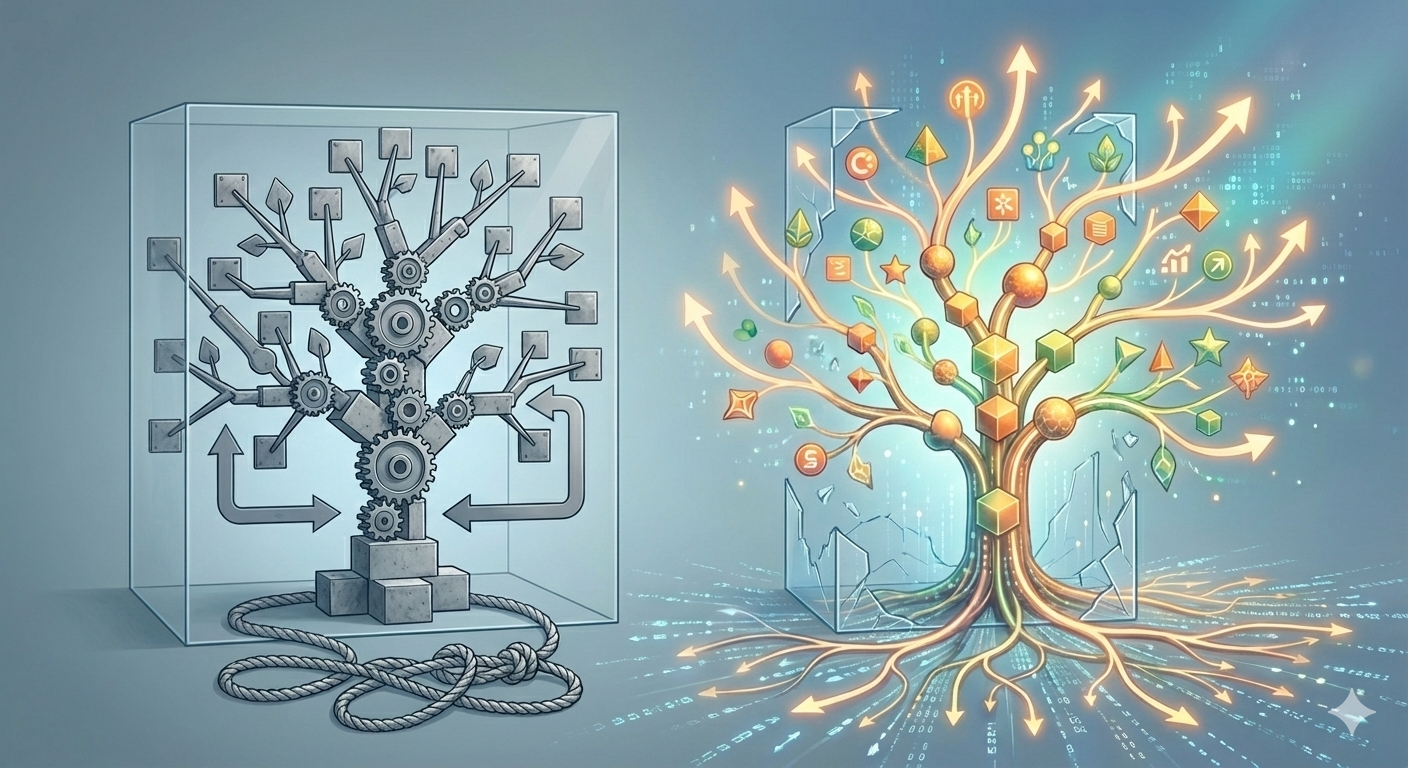

As systems grow, the instinct is to constrain behavior: tighter standards, stricter processes, fewer acceptable ways to do the work. The assumption is that uniformity produces reliability, and that agency introduces too much variance to manage.

It’s an understandable impulse. It’s also one of the most reliable ways to slow an organization down.

I learned this years ago while acting as an architect on two parallel projects, both staffed by offshore teams in India. The teams were similarly skilled, similarly resourced, and working under similar constraints. The only meaningful difference was that they were based in different cities and offices—one in Bangalore, the other in Pune.

The outcomes could not have been more different.

Same Country, Same Time Zone, Different Results

Each evening (U.S. Eastern time), before their workday began, I joined separate video calls with each team. I came prepared. I provided written direction, seed code, and pseudocode with detailed explanations of intent.

This was deliberate.

These were Adobe Experience Manager projects. The patterns I was introducing were not generic or widely repeatable. If they were, the teams wouldn’t have needed much direction from me in the first place. I had standardized ways of communicating architectural intent: how authored content should behave, why certain authoring mechanisms mattered, and how extensibility needed to be preserved over time.

By the time we met each evening, both teams had already reviewed the material.

I opened each call the same way:

Did you have time to review the direction?

Any questions, concerns, or objections?

Are you confident you can be productive with this direction?

With the Bangalore-based team, everyone was physically gathered in a single conference room. All confirmed they had reviewed the work. When I asked for questions, only one person spoke: the Tech Lead. Even when I explicitly invited the engineer assigned to a feature to weigh in, responses were still routed through that single voice.

At first, this looked like hierarchy or politeness. Over time, it revealed itself as friction.

When that team encountered uncertainty, progress stopped. Questions surfaced a full day later, still filtered through the Tech Lead. Small issues compounded. Days were lost—not because of skill gaps, but because the system discouraged individual judgment.

This wasn't a reflection of individual capability. In different moments—one-on-one conversations, informal channels, even sidebar threads—those same engineers showed sharp technical instincts. They had opinions. They saw problems. The structure just didn't give them a natural way to surface any of it. What looked like passivity was actually a learned behavior: the safest move in their environment was to defer.

There was no distributed technical leadership on the U.S. side to absorb this. I was the only technical authority not based in India. The other U.S.-based roles were a Project Manager and a Business Analyst.

When gaps appeared, they landed on me.

I responded by providing more seed code, more scaffolding, and more explicit instruction—not because the problem was architectural, but because the organizational structure left no other path forward.

A Note on Absorbing Dysfunction

Escalation was possible, but the system implicitly rewarded adaptability over disruption. I was new to the role and wanted to prove my worth. In practice, that meant filling the gaps quietly rather than challenging the shape of the team.

Looking back, I know I should have escalated while continuing to push forward—raising the concern without waiting for resolution before acting. That tension—between escalating and absorbing—is one of the harder dynamics to navigate in organizational life.

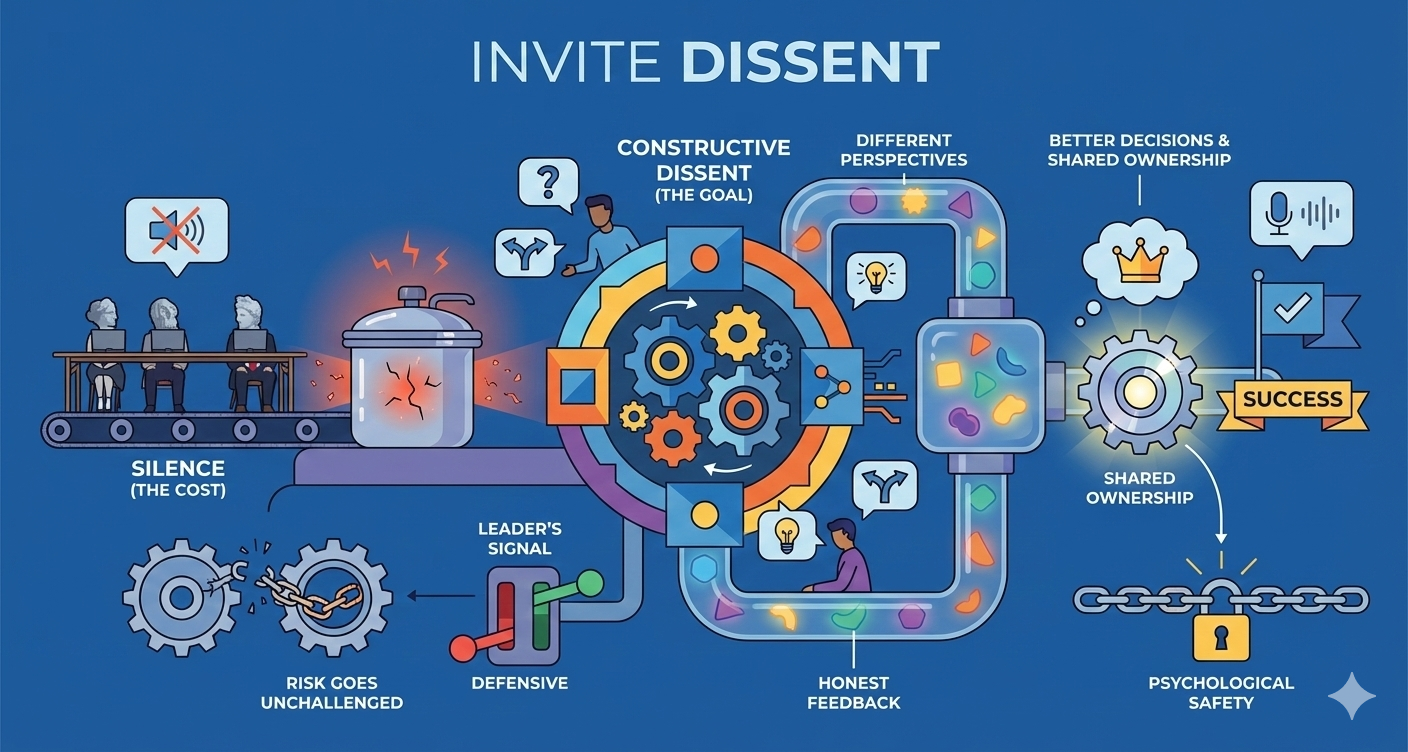

I've written elsewhere about inviting dissent—about how suppressing challenge creates silent failure. At the time, I was on the other side of that equation: a contributor choosing to absorb dysfunction rather than surface it.

I'm not saying I should have blown up the project or refused to adapt. A bit of dysfunction is often just a constraint you operate within. But I've since learned that the best response is rarely absorption or escalation in isolation. It's both: soften the blow in the moment, but raise the concern through whatever channels exist. Move forward as if nothing will change, and advocate so that something might.

That's the posture I should have taken earlier.

A Different Dynamic

The Pune-based team behaved very differently.

On those calls, individuals spoke directly. Each person explained what they planned to work on. Concerns surfaced early. Constraints I hadn’t known about were raised immediately. Sometimes I realized I needed to clarify intent. Sometimes their proposed solutions were simply better aligned with the use case.

When they hit snags, they didn’t stop. They reasoned from intent and moved forward. Course corrections were small, fast, and cheap.

That project finished weeks ahead of schedule.

The Lesson Wasn’t Cultural

Both teams were in India. The difference was not geography, motivation, or technical capability.

The difference was how much agency the system allowed individuals to exercise.

In one office, communication was centralized. Judgment was deferred upward. Safety meant waiting.

In the other, engineers were treated as trusted knowledge workers. The Tech Lead coordinated rather than mediated. Questions were signals, not liabilities.

Distance wasn’t the issue. Agency was the variable.

Why Agency Scales Better Than Control

One of the central ideas in Frictionless is that friction is systemic. It emerges when organizational constraints conflict with how knowledge work actually happens—through interpretation, judgment, and iteration.

Attempts to eliminate error by enforcing conformity often suppress the very signals that prevent failure. Problems don’t disappear; they surface later, more expensively, and with fewer options.

Agency introduces variance—but it also introduces early detection, adaptation, and learning. When engineers are trusted to act on intent rather than instruction, feedback loops shorten and throughput increases.

When agency is removed in the name of safety, systems become brittle. People wait. Work queues grow. Complexity hides in workarounds and silence.

Uniformity is often mistaken for scalability. It isn’t.

Scaling Without Agency Is Just Slowing Down Carefully

The organizations that scale well don’t eliminate variance. They design systems where variance is visible, correctable, and safe. They invest in shared understanding, tooling, and trust—so people can move without waiting.

Agency is not a cultural luxury or a regional gamble. It is a throughput mechanism.

Remove it, and you don’t get fewer mistakes. You get fewer signals, slower recovery, and teams trained to comply rather than think.

At enterprise scale, that cost compounds quietly.

Agency isn’t a risk to manage away.

It’s a scaling tool.

So ask yourself: are your teams slowing down because they lack structure—or because they've been structured out of exercising judgment?